Through the Listening Glass

Saturday, May 3, Museum of Worcester

Sunday, May 4, Old South Church, Boston, and livestreamed

Quartet in C Major for glass armonica, flute, viola, and cello Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741-1801)

Andante

Grazioso (Tempo di Menuetto)

Largo in G Minor for glass armonica Johann Abraham Peter Schulz (1747-1800)

Romanza • The Cuckoo • Pastorale Samuel Holyoke (1762-1820)

Walzer Mr. Augustus (dates unknown)

Trio in E-flat Major for two violins and cello, op. 3, no. 1 John Antes (1740-1811)

Adagio

Rondo (Allegro)

Allegro assai

Adagio and Rondo for glass armonica, flute, and strings, K. 617 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Adagio - Rondo

Washington’s Minuet and Gavott Pierre Landrin Duport (1762/3-1841)

Luci amate a voi Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814)

Dennis James, glass armonica

Suzanne Stumpf, traverso

Sarah Darling and Jesse Irons, violins

Marcia Cassidy, viola; Daniel Ryan, cello

glass armonica by Erwin Eisch, after Ferdinand Pohl

one-keyed Classical flute by Rudolf Tutz, 1988, after Grenser

violins attrib. to Edward Pamphilon, 1677, and by Victor LeCavalle, c. 1800

viola by J.A. Viseltear, 2023, after the Brescian style

cello by an anonymous Belgian maker, c. 1700

The Worcester performance is co-presented by the Museum of Worcester.

These concerts are supported, in part, by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency,

and The Fletcher Foundation.

Program Notes

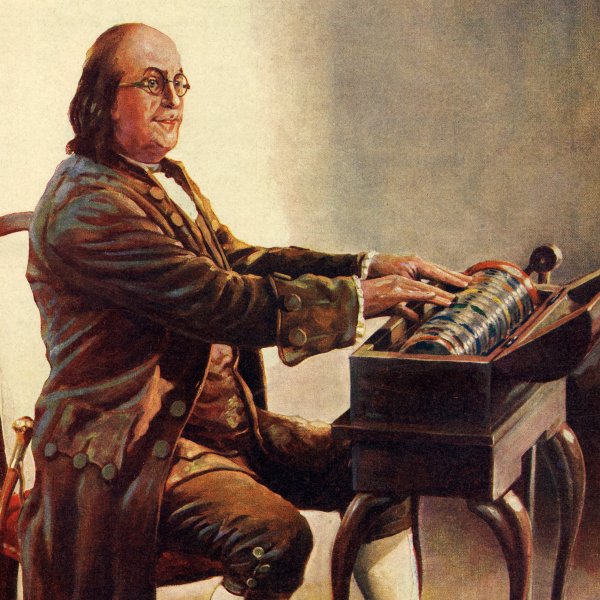

Benjamin Franklin was among the most intellectually and culturally curious of the founders of the United States. While dealing with the tedious and often frustrating work of early American politics and British bureaucracy, Franklin soothed his soul by spending his spare time focused on his favorite leisure pursuit: music. Between 1757 and 1762, he worked on his beloved pet project—his musical instrument invention, the glass armonica—eventually perfecting the instrument to his satisfaction. With the goal of mimicking the sound of “singing glasses” which had been popular in Europe, Franklin arranged a series of glass discs or bowls on a rotating spindle to function like a piano keyboard. Each disc was tuned to a specific pitch by varying the size and thickness of the glass. By

applying pressure to the rims of the discs with wet fingers, players create ethereal tones, described by Franklin as “incomparably sweet beyond those of any other.”

Franklin sought to popularize the glass armonica, sending building instructions to friends and teaching musicians to play, including the harpsichordist Marianne Davies. (She went on to teach the instrument to many, including the future Queen Marie Antoinette.) Marianne and her sister, soprano Cecilia Davies, traveled Europe, bringing the glass armonica to various courts and inspiring many

composers to write for it.

One of many notable composers who wrote for the instrument was the Dresden-born musician Johann Gottlieb Naumann. After travel and work in Italy, Naumann made his mark as a composer of opera, influencing musical activities in Stockholm and Copenhagen before settling back in Dresden where he was appointed Opera Kapellmeister in 1786. He wrote many works for glass armonica, including a set of 12 solo sonatas as well as works for the instrument with chamber ensemble. The quartet featured on this program showcases virtuosic conversation between all of the instruments.

Johann Abraham Peter Schulz was an influential composer in the late eighteenth century, serving as music director at several royal courts in Prussia and Denmark. A composer primarily of vocal music, Schulz’s few instrumental compositions include pieces for keyboard, a violin sonata, some dances, and a Largo for glass armonica that was composed in 1788 when Schulz was serving as director of the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen. (It is interesting to note that in that same year, J.C. Mueller wrote his famous armonica treatise for the King in Denmark.)

The creativity and industriousness of early American composers are underlying currents in this program. In addition to Franklin’s invention, these concerts feature some of the young republic’s earliest composers. Samuel Holyoke was a musician and teacher active on the North Shore of Massachusetts and in New Hampshire. A prolific composer, he published over 700 of his own works.

His two volumes of The Instrumental Assistant are important didactic works for instrumental instruction. We have chosen some of the more sophisticated selections from the publication that reveal the charm and delight of domestic 18th-century music-making.

The first American-born Classical composer, John Antes, was a member of the American Moravian community in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he received his entire musical training. His talent as a craftsman led him to the trades of stringed instrument making, cabinetry, and watchmaking. He traveled to Moravian communities in Germany for ministerial training and apprenticeships in 1764, was ordained a minister in 1769, and undertook missionary service in Egypt in 1770-71. There he composed his only surviving chamber works, a set of three trios which he had published in London in 1790 as his opus 3. They show a lively imagination tempered by fine craftsmanship—admirable work for the “dilettante Americano” as he described himself on the title page of this opus. He also composed a set of string quartets, about which he corresponded with Benjamin Franklin. Unfortunately, these

quartets have yet to be rediscovered.

In May of 1791, just a few months before he began work on The Magic Flute, Mozart wrote the Adagio and Rondo for the unlikely ensemble of glass armonica, flute, oboe, viola and cello. This music, almost unknown to modern audiences, is stunning: it displays that powerful combination of intensity and restraint that infuses Mozart’s late music. The first performance of the work took place on August 19, 1791 with armonica virtuoso Marianne Kirchgässner. Mozart himself played viola on that occasion. After Kirchgässner left Vienna, she never used the original scoring again, substituting two violins for the original woodwinds.

Pierre Landrin Duport was a dancing master, choreographer, and composer. He was dancing master for the Paris Opéra, emigrating to the U.S. after the fall of the Bastille. He worked in many cities throughout the U.S., including Boston from 1793 to 1798. His Washington’s Minuet and Gavott is the opening piece from his United States Country Dances, published in New York around 1800.

German composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt had a varied and inspired life. His father was an outstanding lutenist, and early on Johann Friedrich showed talent as a violinist, lutenist, and singer. He landed his first important musical appointment as Kapellmeister to Frederick the Great at the age of 23, a position he held for almost two decades. Through that period, he also developed relationships with many writers and philosophers, including Goethe and Moses Mendelssohn. His own writings about the French Revolution eventually led to his dismissal by the King, and his importance as a writer became equal to his role as a composer in his day. Musically, he became most known for his operas and lieder—he wrote 1,500 songs using texts by some 125 poets, including Goethe. His lieder are considered to have significantly influenced Schubert. His aria, Luci amate a voi is one of only two known vocal works that feature the glass armonica. Scored for soprano, armonica, and strings, the armonica has a prominent role, beginning the work unaccompanied and providing interludes and textural interest. For these performances, the soprano line is played by the flute.

—SUZANNE STUMPF, DANIEL RYAN, AND DENNIS JAMES